In Romania, the Great bustard (Otis tarda) has reached the brink of extinction. While in the 1950s around two thousand individuals still lived in the country, today only a tiny but viable population survives near Salonta, Bihor County. This is a cross-border population, meaning that the birds use both the Romanian and Hungarian sides – and their survival depends largely on the more than one thousand birds preserved in eastern Hungary, a significant success of Hungarian nature conservation.

In recent years, winter observations suggested that the number of bustards in the region might be increasing, as ever-larger flocks were seen. In reality, the situation is far less encouraging: these data refer to wintering birds, not breeding ones. The breeding population, on the contrary, is declining because, among other threats, changes in agricultural practices are destroying and reducing available nesting habitats.

The Great bustard is originally a bird of open grasslands, but much of these areas has been ploughed up. Although it can nest in crops such as cereals or alfalfa, intensive farming often causes breeding to fail. The use of chemicals, early mowing and harvesting can destroy eggs and chicks, while conventional arable farming does not provide enough insect food for the young, which rely entirely on it. Large, homogeneous arable fields are therefore practically uninhabitable for the species. Added to this is the fact that the grasslands around Salonta – and in Romania generally – are heavily overgrazed. This not only causes increased disturbance, but on the short, grazed pasture bustards cannot nest, and insect availability is also poor.

A missed opportunity

For years, the Milvus Group has been working to promote bustard-friendly farming practices in Romania. In 2018, based on our recommendations, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development launched an agri-environmental scheme for the protection of the Great bustard. Its goal was to encourage farmers to manage arable land within bustard habitats in a wildlife-friendly manner, or even to convert lower-quality farmland back into grassland. Although the scheme was sound from a conservation perspective, the support payments were too low, so very few farmers joined. A few years later the programme was discontinued – with dramatic consequences.

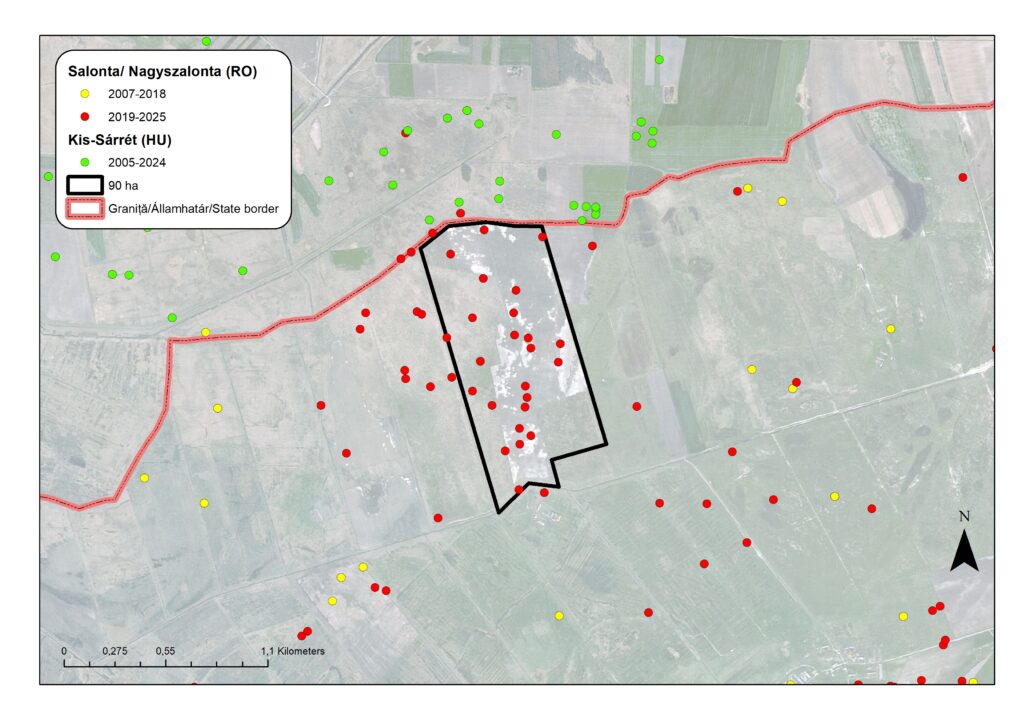

A telling example is that of a farmer who enrolled around 90 hectares of arable land into the grassland-creation scheme for Great bustard conservation. The area, initially weedy and chemical-free, was soon colonised by bustards: we observed displaying males, several nesting attempts, and in multiple years small groups of females leading their chicks – known as “nurseries”. The farmer did not use pesticides and refrained from mowing during the breeding season, so the area became a genuine refuge for the species.

However, this type of support ended in 2022, and this year the farmer – under economic pressure – ploughed up the grassland and sowed winter cereals. The once thriving habitat has practically disappeared. With a single decision, Romania lost perhaps its best functioning breeding site for the great bustard.

What is the lesson?

This case clearly shows that conservation-motivated programmes only work as long as consistent support and incentives are provided. Bustard-friendly agriculture would benefit not only the species itself but also the ecological diversity of the landscape – yet none of this can reasonably be expected from farmers without adequate economic incentives. Unless Romania reverses the degradation of the last remaining great bustard breeding habitats – for example by reintroducing a properly functioning agri-environmental scheme, following the proven models of Hungary or Austria – the great bustard may soon become extinct as a breeding species in the country.